As a young medical student, in my early 20’s, I wasn’t particularly emotionally mature. I grew up in an East Indian household. Classically, my father – my main role model – dealt with life by being the epitome of stoicism. He’s the rock. Calm under pressure. Never really expressing signs of vulnerability, and sending the message that any such signs were displays of weakness.

Emotional control was strength. As such, I internalized those ideas. Remaining cool and detached from whatever life threw at me. If there was sadness, it was kept private.

At the beginning of medical school I didn’t really know how a physician was “supposed to” act.

But I took my preset model of stoicism and applied it to the medical model. This was reinforced by lectures on “professional detachment”. It was the doctors job to keep a professional distance from a patient. Thus, by getting too emotionally involved in the care of a patient we are bound to lose our objectivity.

Without objectivity, we won’t be able to be the calm, rational decision maker. The one who is equipped to make the right decision at the right time. Excess emotionality will put us on the road to burnout. It will seep into our personal lives and we’ll take the sadness of our work home. The so-called mature physician is able to keep a distance between his personal and professional life.

At least, this is what I was led to believe.

My first death

When I experienced my first patient death, I wouldn’t let anyone know that I felt any emotions. I was called to the bedside of a patient taking their last few breaths. A third year medical student, on call, watching for the first time the long slow gasping of agonal respirations. And then they stopped.

Just me, him and a nurse. Middle of the night. His last moments…..and then nothing. An elderly man with a terminal diagnosis. And while we had known that this patient was bound to die, it was another thing to actually SEE him die.

I felt a lot in that moment. Sadness, anxiety, shock, confusion. But I’ll be damned if I let anyone know what I was feeling.

On the outside, I’m sure I exhibited a measure of calm and detachment. I’d known it all too well. This didn’t bother me. Or so I told myself. I could handle anything. Dealing with death was just part of being a doctor anyway and a good doctor stays cool under any circumstances.

So I never mentioned it to anyone, kept my cool, and carried on.

Don’t show emotion. This was my practice for most of my early medical career. Be “tough”. I eventually chose to specialize in emergency medicine. There were many factors in that decision. One of the biggest appeals was that I witnessed ER docs staying composed and cool in the most stressful of situations. Similarly, I wanted to be like those guys (and gals).

Forget emotionality, I wanted to keep it together under the extremes. Laugh at stressful situations. At that time I thought I am in control of my emotions and emotional displays were for the weak.

And then it all changed.

In 2016, I went to South Sudan. My second medical mission with the humanitarian organization Medicines Sans Frontiers (MSF or Doctors without Borders). I spent four months in an internally displaced persons camp that hosted about one-hundred and twenty thousand people.

Although we were doing a lot with the resources that we had, the conditions were pretty rough. We witnessed a lot of death. Mostly children.

Imagine witnessing a child take its last breath. Every day. Attempt a futile resuscitation. Explain what happened to a shocked mother who put all their faith in your Western trained hands. It wasn’t supposed to be like this.

One of the first words I learned was the South Sudanese (Nuer) word for sorry – “Malesh”.

Listening to her scream. Wail. Throw herself to the ground in that extreme African display of mourning. Some combination of hysterical crying and shrieking.

Day after day of the same. And initially I felt….well, nothing. I even talked to a colleague about it. Had I blocked my ability to feel so much that I couldn’t even feel sadness in the saddest of circumstances? Or was I just too busy trying to keep things afloat that I kept my emotions locked up for another day? I still had to work, after all.

Was I capable of feeling anything at all?

That all changed

One week before I had to leave. I had to give a speech, in front of the entire national staff, thanking them for their hard work and leaving them with a few moments of inspiration.

I stood there, in front of the group. About one-hundred and fifty South Sudanese national staff and a few expats. We’d just spent months together. Living here in this camp, in the middle of nowhere, trying to keep people alive in what was seemingly a hopeless situation. I was leaving back to my comfortable home. My colleagues couldn’t return back to their’s. I stood in front of the crowd, looking at the smiling faces waiting to hear me speak. I felt my armour crack.

And as a result, for the first time in my life I couldn’t keep myself composed.

I started to speak and a gush of emotions came pouring out. There I was…..In front of this crowd…..my stoic self.. …..stood and bawled uncontrollably. When I tried to speak, the tears worsened. I stool and cried in front of my colleagues for what seemed like an eternity.

I eventually bumbled through a difficult speech. It was well received. Most honest displays of emotions truly are. But something in me had changed. During the rest of my time there I couldn’t keep my emotions in any longer. I cried for my patients. My coworkers. And the country. I went home. Inevitably, I cried some more.

In the end it was a good thing. I needed to do it.

Since that moment, I’m better able to access and express those emotions when they present themselves. No longer do I keep things in the way I used to.

And you know what? It’s impacted my relationships with others in so many positive ways.

Today, I’m still not an overly expressive person like I was for those few weeks at the end of my trip. However, I’d like to think I’m somewhere in between.

So now when a patient dies…. well……sometimes I cry.

Is that okay?

There are a couple sides to this debate.

On one side, the stoic physician. My former self. There are those that consider crying in front of a patient as “unprofessional”. We shouldn’t display any signs of strong emotions. It affects our ability to think rationally. The stoic professional can and should withstand anything.

Others would say that it’s not a display of emotion that’s a problem, but the degree of emotion displayed. In other words, a little is okay, but too much isn’t. In the end, it’s about the patient and if the physician was too emotional it might detract from the families ability to grieve. This is the ultimate priority.

The flip side. Doctors are simply, human beings. Whether or not we display our emotions, we certainly feel them. Patients are often comforted knowing that doctors feel empathy and sadness at loss. Patients expect their doctors to care, often think they don’t, and find some relief when they see you do.

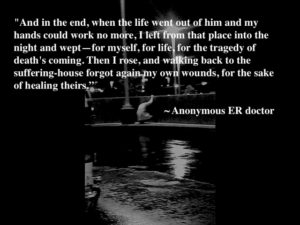

A few years ago a picture of an ER doc, crouching down outside the hospital after a failed resuscitation went viral. It showed the emotional side of medicine, a side people don’t often get to see. It surprises the public to learn how much our work can really affect us.

There’s reasonable rationale on both sides of the coin.

In my own experience, I once thought stoicism was the only way to go and then, I found that there were some emotions that I couldn’t and shouldn’t keep held in. And as such, I have greater empathy and understanding with those for whom it is the same.

Perhaps what it comes down to is what physician you would you want at your bedside? Or at the bedside of your loved one?

The cool, rational, detached doctor ….or the warm, empathetic, teary-eyed one?

Which of those people you end up being isn’t always in your control. Sometimes it’s unpredictable. Our responses are a complex pattern of beliefs, experiences, and behaviour. I’m not here to tell you how to feel and how to behave.

But I will say this.

From my experience, I really do think that the worst thing we can do is suppress sadness when it comes up on our shifts. Keeping things inside or pushing down emotions eats away at us in little ways. Inevitably, it affects our health and wellbeing in ways we don’t fully understand.

So if you have the tools it’s really healthy to acknowledge how you feel in the moment. If you react to those feelings by crying, then that’s a genuine honest way to process those feelings. You shouldn’t be ashamed of doing it.

If you don’t think you can control your reaction to your feelings, or it becomes too strong, then it should be okay to excuse yourself for a moment, feel your feels, compose yourself and then return.

Grieving is a normal reaction to a dealing with sadness and loss, and doctors should be given the space to grieve.

It’s okay to cry sometimes. Crying is simply human.

And really, that’s all you are.

2 comments

Thank you for posting your about your experience. I salute you, and think we need more emotional exchanges in our day to day transactions, particularly when words alone fail the situation.

Thanks for your reply Kim. I really appreciate it.

I think that’s the whole idea for me. Am hoping to bring a little more humanity and honesty to the medical experience. We’re all just trying our best, sometimes we’re not doing that well, and it’s okay to acknowledge that.

Thank you for reading!